It was a relatively quiet evening of dining and theatre-going in New York City when Times Square suddenly erupted into chaos. More than a dozen were injured [1] as a throng of tourists fled what they believed to be an active shooter [2], some even pounding on doors of Broadway theatres [3], hoping to be granted shelter. It wasn't gun shots but a motorcycle backfiring that caused the stampede. Yet the reaction seemed inevitable in a nation still reeling from one of the deadliest weekends in its history. Twenty-two people had died in a mass shooting at a Walmart in El Paso, TX [4], a few days earlier on Saturday, Aug. 3. Thirteen hours after that, news broke that a gunman had murdered nine people in 32 seconds [5] after opening fire in a popular nightclub district in Dayton, OH.

The anxiety that surfaced that evening in Times Square has been simmering for some time [6], especially among young people, who have come of age in an era when mass shootings and active shooter drills are routine. In online forums, teenagers write anonymously about the realities of growing up in this climate: how they instinctively check for exits in public spaces and startle over the smallest things, how carefully they navigate relationships with peers they're afraid could turn violent, how young they were when they first realised that they may have to sacrifice themselves to save someone else.

Research suggests that these experiences are more universal than they would seem. In a survey conducted by the American Psychological Association, 75 percent of Gen Z youth — who already suffer from symptoms of anxiety and depression in greater numbers than any previous generation — cited mass shootings as a significant source of stress [7]. For many, that fear starts in the place they should feel safest: at school. "It's been happening everywhere [8]," Paige Curry told reporters in May 2018, after a shooting at her high school in Santa Fe, TX, left 10 people dead. "I've always kind of felt like eventually it was gonna happen here, too. So I don't know. I wasn't surprised, I was just scared."

A Moment That Defined the Mass Shooting Generation

In April 1999, the tragedy at Columbine High School in Littleton, CO, shocked the nation. Two young men fatally shot 12 students and a teacher [9] and injured two dozen more, before taking their own lives. The images of teenagers, some wounded, fleeing the school were seared in the minds of those who were old enough to understand what had happened — and then for years, seemingly, Americans went about their lives without worrying that history would repeat itself. "[I had] heard of Columbine, but it just seemed like a random act of violence to me, not something that would ever happen again, let alone regularly," Katie Parzych, 22, told POPSUGAR.

Then, on Dec. 14, 2012, a gunman killed 20 first-graders and six educators [10] at Sandy Hook Elementary in Newtown, CT. This time, the students being led out of the school were just young children. An image of an anguished young woman screaming into her cell phone [11] went viral. And the conversation turned from shock and horror to how schools could keep kids safe.

After Sandy Hook, lockdown drills became a regular, bimonthly practice at Katie's high school in nearby Massachusetts. She distinctly remembers the instructions students received: for example, never to open the door to the classroom for anyone once it had been locked. "Police officers would come around and jiggle on the door handle, begging to be let in, but the rule was to never open the door again," she said. "When the drill was over or in the event of a real incident, the police would have universal keys and come unlock it themselves, not ask for anyone inside to do so."

While the drills conducted in schools are well-intentioned, they can also be frighteningly realistic. Sarah, now 20 — who declined to give her last name — was a student at Central York High School in Pennsylvania in 2013 when the school made headlines for what was called the largest active shooter drill in the US [13]. "There were students selected to be victims with fake injuries for the EMTs to 'treat,' mostly in some specific first-floor hallways where the shooter was supposed to be. The rest of us were huddled under counters in the dark," she told POPSUGAR. Sarah knew it was a drill, but she recalls wondering what she and her classmates would do if there actually was a shooter in the school. They were on the second floor — could they still escape from the windows?

"I try not to think too much about it because I don't want to live in fear. But I also know it could very well happen here."

For the first week after that massive drill, Sarah said things were "touchy" at school. "Kids kept saying maybe someone would see the news about the drill and decide to test our preparedness. Mostly it was the halls or common hours that were nerve-wracking, where it was already chaotic," she said. Sarah made sure to tell her parents she loved them every day, "just in case."

This apprehension — that the next shooting could be the one that threatens their own lives — remains a quiet but near constant presence in many students' minds. "I don't know anyone who isn't at least somewhat worried or anxious that our school will be next," Laura, a high school sophomore in a San Francisco suburb who declined to give her last name, told POPSUGAR. "On the one hand, I try not to think too much about it because I don't want to live in fear. But I also know it could very well happen here, and I want to be prepared in case it does." Laura said she constantly checks her phone to make sure it's on silent, since a text could alert a shooter to her location; she also avoids leaving class because of the possibility that someone will open fire while she's in the hallway, separated from her classmates and teachers.

Why Safeguarding Schools Isn't the Answer

"School used to be a safe place," Ashley Hampton, PhD, a licenced psychologist in Alabama who focuses on trauma, told POPSUGAR. "Most of your day was at school, so even if your home life wasn't great, school was a place where most kids felt safe and cared for. Now it's become a place of terror." Like many experts, Dr. Hampton is concerned about the toll this could take on vulnerable children and teens, and she believes lockdown drills may do more harm than good.

"They are kids. Their biggest fear should be taking a test that they forgot to study for, not how to keep themselves safe if a gunman entered the school."

As a high school student, Katie took comfort in the drills, but things changed when she began substitute teaching fifth-graders in Connecticut after college. "There is such a fine line between making sure the kids understand the importance of lockdown drills and absolutely scaring them," she told POPSUGAR. During drills, she would rush all the students to the corner of the classroom, shut the blinds, and lock the door. There would inevitably be giggles and whispers as the children tried to entertain themselves in a cramped corner for 20 minutes. "It was tough to figure out how much to explain to them about why they needed to be silent," she said. "I always seemed to have one or two students who would sit next to me and just hold onto my arm. They were trusting me to keep them safe from whatever could possibly be going on outside."

Katie encouraged her students to come to her or the school guidance counselor if they had questions or needed someone to talk to following the drills, and often they did. "My biggest fear was how I would keep them safe and quiet without causing panic if the real thing ever did occur," she said. "They are kids. They shouldn't have to know about all of this. Their biggest fear should be taking a test that they forgot to study for, not how to keep themselves safe if a gunman entered the school."

Image Source: Getty / Timothy A. Clary [14]

Image Source: Getty / Timothy A. Clary [14]

It's the weight of that responsibility that concerns experts most. "These drills are really instilling a sense of fear in kids," Dr. Hampton said. "We're training kids to think there's always going to be someone out to get you, and you need to be on guard all the time, which creates anxiety and post-traumatic stress."

41 percent of Gen Z youth report that the security measures in schools have done nothing to alleviate their stress about shootings.

Michelle Paul, PhD, director of The PRACTICE [15] at UNLV and president of the Nevada Board of Psychological Examiners, explained that there's no data to indicate whether lockdown drills are effective at reducing the number of fatalities in the event of a school shooting. However, in the APA survey, 41 percent of Gen Z youth reported that the security measures in schools had done nothing to alleviate their stress about shootings, while 22 percent said they had somewhat or significantly increased their stress.

Until there's more research, Dr. Paul believes personnel should emphasise that drills are done for the purpose of being prepared, while also reassuring students that they'll be taken care of in an emergency. "What people need are reminders that the system is going to do what it needs to do to promote safety," Dr. Paul told POPSUGAR. "The staff are the ones who have to be the best trained and send the message, 'We've got you. We know what to do inside and out.'"

For younger children, Dr. Hampton recommends folding active shooter drills in with other drills, such as those that prepare students for natural disasters like tornadoes or earthquakes. By the time kids reach high school, the intention should be to empower students, rather than inadvertently signaling that a school shooting is inevitable. "Tell them, 'Here's who you talk to if you see something suspicious,'" she said. "That's something that sets them up for life because mass shootings aren't just happening in schools. They're happening in movie theatres, churches, and other public spaces."

A Call to Action, Before It's Too Late

The unpredictability of mass shootings may be the most compelling argument against lockdown drills. While Sandy Hook was a flashpoint in the debate surrounding gun violence, mass shootings had been on the rise for some time, both on and off campus. Five years earlier, a shooting at Virginia Tech claimed 32 lives [17]; five months earlier, 12 people were fatally shot in a movie theatre [18] in Aurora, CO. According to The Washington Post's mass shootings database [19], mass shootings occurred approximately every six months prior to Columbine [20]. That window narrowed in the years that followed, shrinking to every six weeks after the 2015 massacre at a historically black church in Charleston, SC. In addition to becoming more frequent, mass shootings have grown increasingly deadlier: San Bernadino, Orlando, Las Vegas, Parkland. While there are a number of reasons for the uptick — including a desire for fame on the part of mass shooters [21] and a growing threat from white supremacy [22], among other things — research shows that there were fewer mass shooting-related deaths before the assault weapons ban expired in 2004 [23].

"Rather than holding drills and instilling fear, we need to address the actual issue of gun responsibility."

Emily Cantrell, 36, was near the stage at the Route 91 Harvest Festival in Las Vegas [24] in 2017, when a gunman with an arsenal of modified, semiautomatic weapons opened fire on the crowd. Though she has participated in numerous crisis communication planning meetings and active shooter drills as part of her job organising large festivals in Seattle, "I don't know of any type of drill that could have helped or prepared us," Emily told POPSUGAR. "No one knew where the gunfire was coming from, and there is no way to protect yourself when the shooter is 32 floors up and nearly 500 yards away [25]." Asked what she wants for the next generation, her answer was simple: "Rather than holding drills and instilling fear, we need to address the actual issue of gun responsibility."

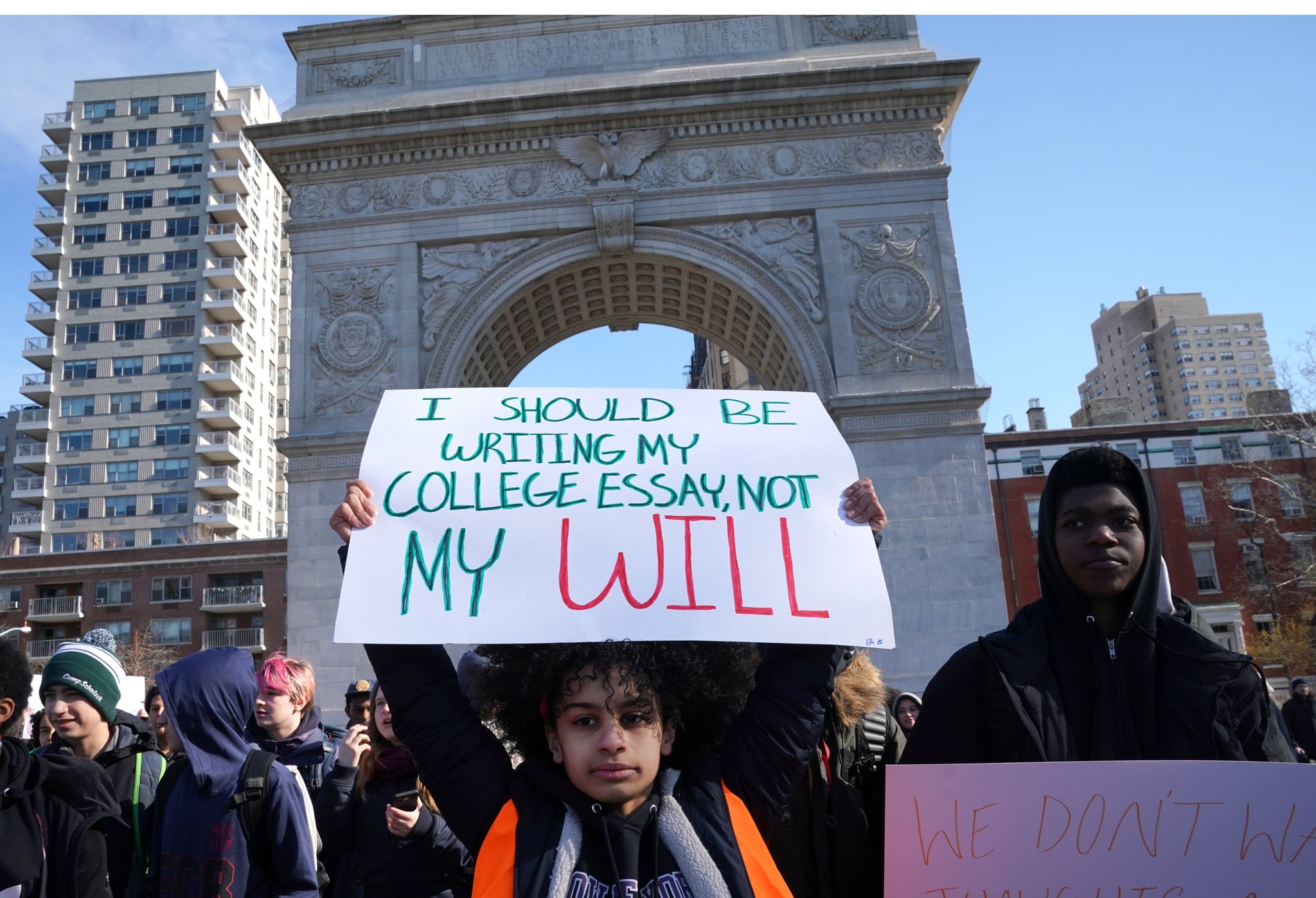

As evidenced by the surge in activism [26] following the 2018 shooting at a high school in Parkland, FL, young people overwhelmingly agree that lawmakers should tackle the problem [27] of seemingly unfettered access to guns. "Kids can buy guns before they're legally allowed to drink. To me, that's absolutely mind-boggling," Ashley, a sophomore at the same California high school as Laura, who also declined to give her last name, told POPSUGAR. "I'm not saying the solution is to get rid of the Second Amendment, but why can't there be some sort of middle ground? Universal background checks and closing the gun show loophole seem like common sense, and I don't understand why this is even a topic of debate."

Sarah grew up in a home with guns, though she has never personally owned one herself, and she also supports gun reform, including licencing laws that already exist in some states. "But we never seem to change anything after mass shootings," she said. Until progress is made on the national level, she'll continue doing what she's always done: "I treat any confrontation with a stranger like they could have a gun," Sarah said. It's a uniquely American way of life.