What It's Like in Italy During the Coronavirus Outbreak

I Live in the Coronavirus Red Zone in Italy and Please, Please Stay Home

Image Source: Getty / Ivan Romano

At the beginning, it was far away. I used to see it flowing on the news, but Wuhan, China, is not close, so even a hypochondriac like me wasn't paying attention. I was way more interested in the Serie A football tournament and who would win the San Remo festival. Then, suddenly, the first case in Rome. Oh, it's just a couple of old guys in isolation, and so we minimise everything being said about the coronavirus. Here in Lombardy, Italy, we keep going to work, French kissing, shopping, and going to concerts, not paying attention at all to COVID-19.

A few days later, there is another case. This time it's only 40 km (25 miles) from my house: a young guy, someone a friend of a friend has met maybe once. The news comes, loudly, but we still tell ourselves that it's just "slightly worse than an ordinary flu." We are 30 years old, of course nothing can happen to us. The day after, the infections rise to dozens, and so we start being scared.

Schools close. The news tells us about empty supermarkets, while Italy becomes incredulous. Some say they don't want to stop their normal lives and use hashtags like #MilanoNonSiFerma (Milano doesn't stop); awkward video campaigns tell us we can beat this. After all, we are Italians, the people of hugs, big feasts, and Sundays with our family, all together.

At Gummy Industries, the creative agency in Brescia, Italy, where I'm a partner, we find ourselves in the middle of the red zone as the news now calls it — we must decide what to do. My partners and I are faced with an ethical decision: what do we do for our employees? We discuss it at a Sunday virtual meeting and decide to react before we're told to. We invite our employees to stay home to avoid physical contact with coworkers and avoid being exposed to the virus.

First, there's one, then four, eight, all of a sudden 20. Our brothers, sisters, cousins, neighbours start getting sick.

Day after day, we stay home, and things get worse. A lot of people around us start getting sick. Nothing serious, luckily, but friends have fevers and sore throats. First, there's one, then four, eight, all of a sudden 20. Our brothers, sisters, cousins, neighbours start getting sick and hundreds of people are now in intensive care, where there are not enough ventilators and laundry rooms are being transformed into spaces for hospital beds. We see the efficient healthcare of Lombardy, Italy, a worldwide example of free healthcare, failing.

Infections grow day by day, but we know more people are infected than those we know tested positive. Maybe there are 10 people walking around with no symptoms spreading the virus, or maybe 100, or 1,000. Maybe I'm sick, too. Maybe this faint pain I feel when I breathe deeply is something. I don't know. I really don't know and that's the problem.

Image Source: Michele Pagani

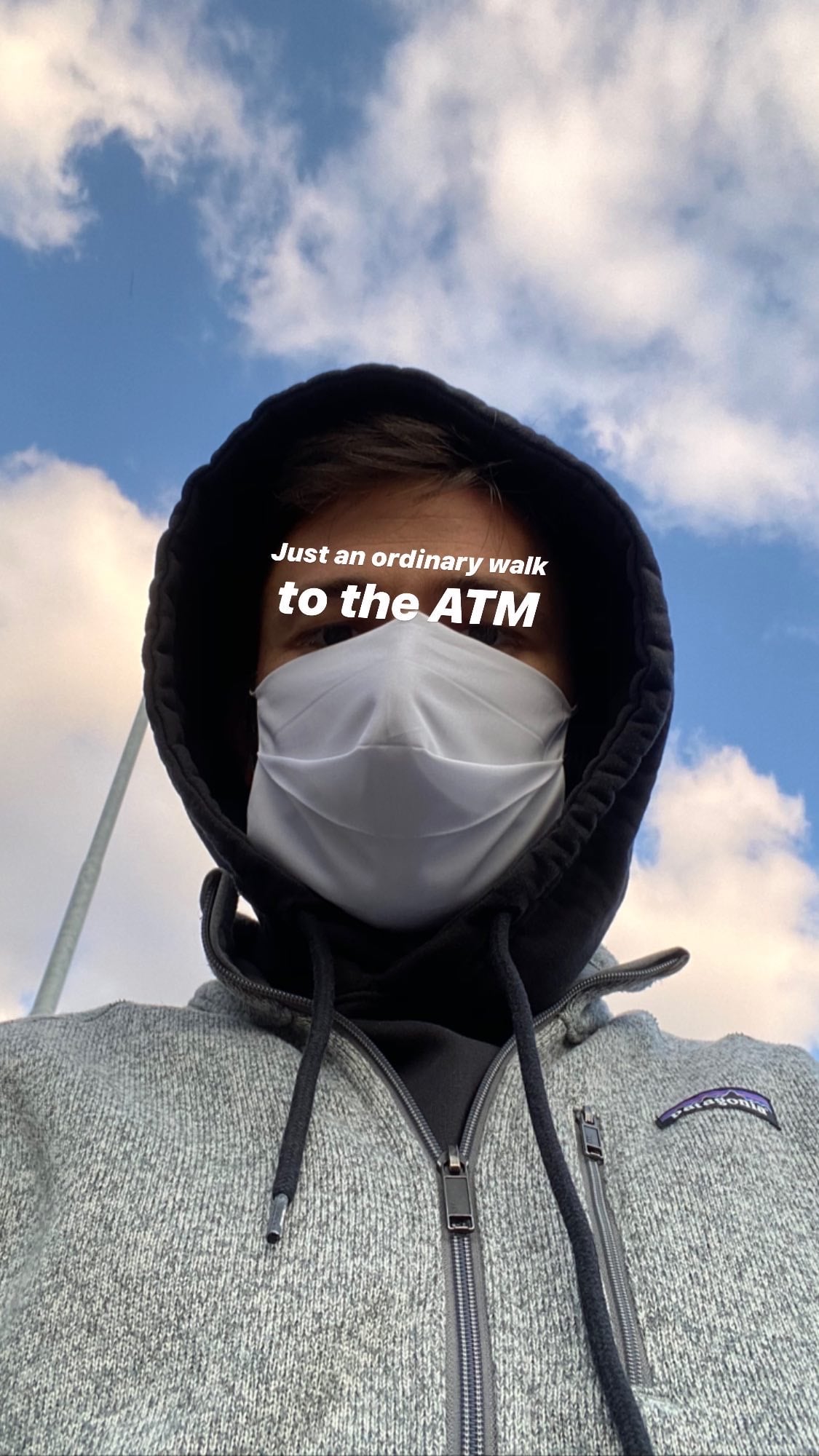

I talk to my family on FaceTime. I don't go out anymore, except for a run in solitude or to go to the pharmacy, always wearing a facial mask and compulsively sterilising my hands with sanitiser.

And then, one day, the government decides to do something, forcing everybody to stay home. With a speech to the nation, on all networks, our Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte says that bars, restaurants, and factories must close. The Italian Stock Exchange crashes, but online, everything is as usual — memes, selfies, this time wearing masks, Instagram Stories. It's odd. I can't say I'm sad or bored. I just feel strange, between alienation and waiting for something I hope is not going to happen.

I wake up, drink a coffee and I'm already in front of my laptop, on that table that I usually use for having breakfast that now is what I call "the office." I've done it maybe hundreds of times in the past, but this time is a totally different story. I make calls and presentations, I chat and scroll Facebook, I hope that some good news are coming. I try to order groceries online, but they won't come for two weeks, and so I wear my apocalypse uniform and go to the supermarket, in a scenario that looks like the one I saw many times in the movies I love. I buy stuff, looking like I'm waiting for zombies to find me. Masks are sold out, so are hand sanitisers. In the hospitals, it's a tragedy. People are left to die: grandparents, parents, brothers, and sisters. There's no room for everybody.

Gummy starts a Facebook show — The Gummy Daily is what we call it — 15 minutes a day where we tell the world how we're living and working through these weird moments. We do it to muster courage. We do it to keep going, "meeting" new people, sharing thoughts, encouraging curiosity. We tell the world that things go on. We live in a movie. We try new things. I start making pizza, doing Tabata, tidying up my closets, doing yoga, and meditating. I buy €200 worth of Playstation games.

Image Source: Michele Pagani

This new routine is tolerable, almost pleasant. What is not pleasant at all is the growing background of infections and concerns and the noise of ambulances, that we'll only get rid of with patience and trust in our neighbours.

I write to my friends in the UK, saying do not underestimate this thing, wash your hands, stay far from people. Because luckily we are in 2020, and knowledge spreads faster than viruses.

And so I am astonished when I read of other countries, where everything takes me back to two weeks ago, when we were so naive and the virus "was just a flu." I write to my friends in the US, UK, Spain, and Sweden, saying to be alert, stay home, do not underestimate this thing. I tell them to wash their hands, stay far from people, and go out only when needed. Because luckily we are in 2020, and knowledge spreads faster than viruses.

This is not a good story and we weren't ready for it, but it's teaching us many things. Maybe we are learning a new sense of community, the value of everyday life, of freedom, of loved ones. Maybe this thing is dividing us, while joining everybody in a common fate. I hope that the extraordinary job of doctors and nurses and all the other heroes who are helping us will teach us about living outside self-interest. I hope it'll teach us that we are strong and that at the end we can all recycle, respect diversity, and give up something for someone we don't know.

I wonder if at the end of this story I'll be able to better understand my dad, who often says "ho fatto la guerra" or "I went through war," a sentence that I've heard many, many times from him about World War II. I wonder if at the end of this story we'll all have "fatto la guerra" with lots of patience and compliance with rules (and PlayStation and Netflix). It's the least we can do.