Short Hair Personal Essay

Short Hair on a Woman Is Still Considered Radical — and I Love It

There's something about the slow float of a chunk of hair as it drifts from scissors to floor. Do the locks represent a loss, a rebirth, a shame, a reclamation of power? When it comes to my hair, it's usually some confluence of the above.

The author the day she cut her hair. Image Source: POPSUGAR Photography / Lindsay Miller

The first time I cut my hair short, I was 14. I had just discovered punk rock. I had just gone through what I thought was my first "real" breakup with my first "real" boyfriend. I was about to start high school and was roiling over with anguish and excitement at this gleaming opportunity to reinvent myself: as someone cool, unaffected, edgy, and maybe the kind of girl people would say was "pretty, even with short hair." My shaggy, cherry-Coke-red pixie, achieved in the garage-turned-salon of my mother's hairstylist Annabelle, hinted at a version of myself that I hoped simply had yet to emerge. The version of myself that was autonomous and daring and untouchably self-assured; things that are torturously difficult to actually, really be as a teenage girl. (Or a full-grown adult person, for that matter.)

The second time I cut my hair short, I was 33 and ready for a radical change. I say radical with intention. I cut my hair in the first year of Donald Trump's presidency. This was not coincidental, but I can't quite position my haircut as some grand statement against the crass misogyny and retrograde gender politics gripping the nation. Real talk: I had a lot of breakage thanks to my obsession with achieving an almost-white level of bleach blond, which was a motivating factor, and I already knew I could more or less "pull off" a short crop thanks to my teenage experiment. I'm not above vanity. But I also increasingly did not care about being agreeable when it came to conventions about what a woman should look like or do to be pleasant, to fit right in.

Audrey Hepburn in How to Steal a Million. Image Source: Everett Collection

Throughout recent history, short hair on women has served as a signal. It is not strictly adversarial or controversial — though it is often those things. It can just as easily communicate naiveté and whimsy, as it did for ingénues like Twiggy and Mia Farrow in the mid-'60s, crops on the cusp of the sexual revolution. (A widely believed rumour around the time of Farrow's chop was that her then-husband, Frank Sinatra, was so put off by the look that it prompted him to file for divorce. Farrow corrected the record just a few years ago, pointing out that she actually cut her hair before they even wed. But the fact that the gossip struck people as so easy to believe sure is telling.)

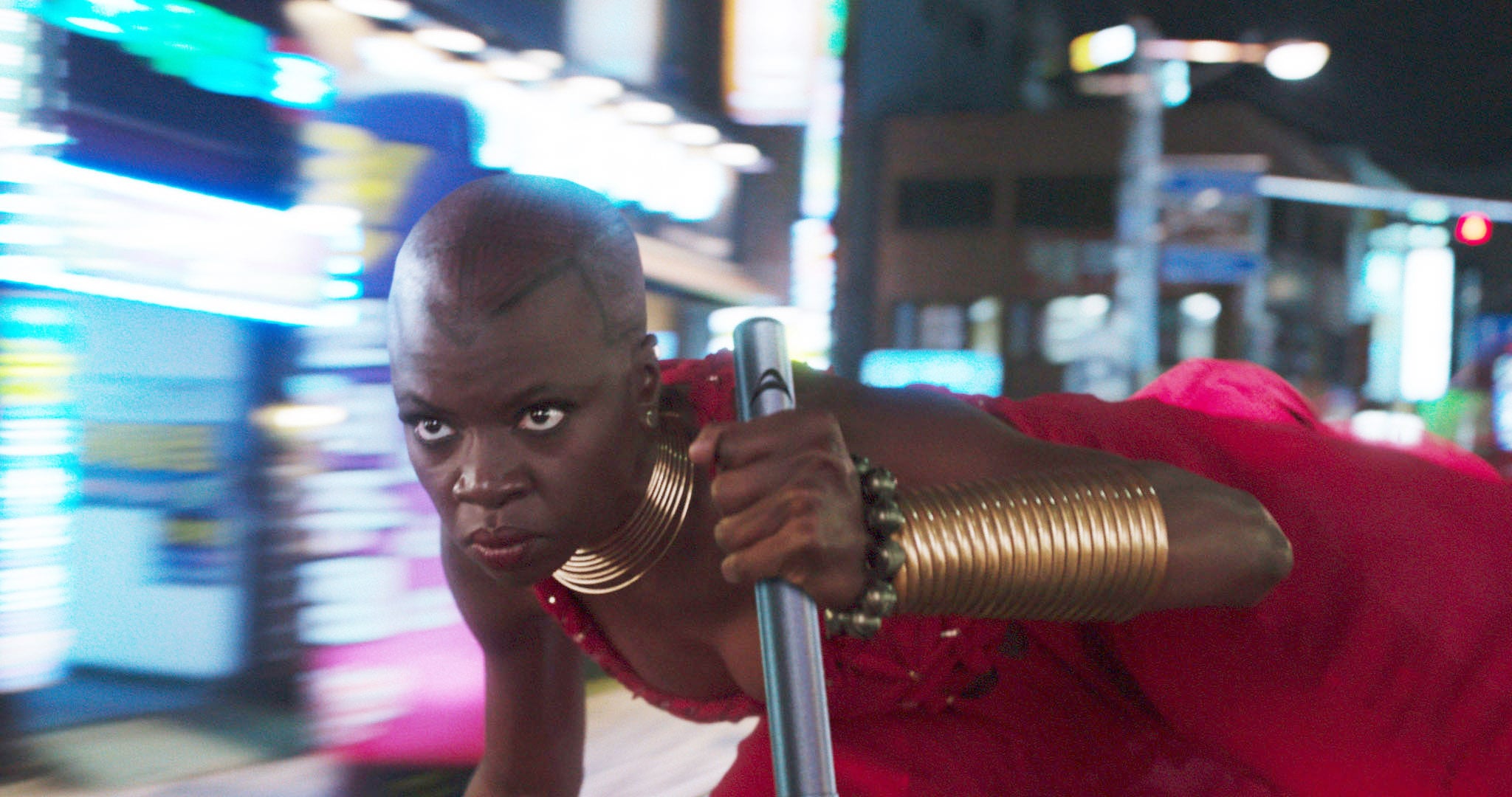

Danai Gurira in Black Panther. Image Source: Everett Collection

Short hair can suggest a remote sort of glamour and a Manhattan-croissant-breakfast-in-pearls sophistication, as it did for Audrey Hepburn in her heyday. It can radiate a ferocious sexuality, like Halle Berry's dripping-wet Bond girl locks as she emerges from the ocean, a knife holstered suggestively at her hip. Or it can broadcast a challenge to authority and the status quo, like activist-to-be-reckoned-with Emma Gonzalez's buzzed pate. Sometimes, a bare scalp on a woman serves as an ultimate expression of resolve, identity, and power. (Hello, Danai Gurira and the warriors of Wakanda.)

Just a quick plug to remind everyone that the March is in 2 DAYS !!! we are all gonna make history together :'-)https://t.co/06H93Gu6D8 pic.twitter.com/bfGRykml6Y

— Emma González (@Emma4Change) March 22, 2018

Short hair on a woman can do more than one of these things at once, but rarely does it fail to do at least one of them. As Joan Juliet Buck expressed in her excellent, if now slightly dated, 1988 essay for Vogue: "Short hair makes others think you have good bones, determination, and an agenda." Emphasis my own.

In fact, the idea that women "should" have long hair has been so universally, culturally pervasive, it still persists in the relatively gender-fluid, nonconforming, #NastyWoman year of 2018. The surprise and dissonance that a woman with a pixie cut or buzz or other close crop still manages to inspire was made explicit on this season of The Bachelor, on which Bekah M. sported a wavy cap of supershort brunette locks.

Bekah M. of The Bachelor fame. Image Source: ABC

Bekah was the first woman in 22 seasons of The Bachelor to have short hair. First! In 22 seasons! Sure, that's a testament to the backward, heteronormative sexual and gender politics of that particular franchise — but we can't ignore what that franchise says about the very society it reflects and attracts on its screen. A woman with short hair competing for the love of the nation's most eligible bachelor was so unexpected that the show apparently treated the oddity as the defining aspect of her personality, which Saturday Night Live gloriously spoofed in the following sketch:

"Tell me something about you," the pretend bachelor coos at the pretend Bekah M.

"Well, I have short hair," she says in a shrieking whisper. "Isn't it the weirdest thing you've ever seen in your whole life?"

"Yeah. But somehow I still like you."

"Yeah. That's because I'm barely 21."

Hair is still innately tied to an old-school idea of femininity and womanhood. Again, just look at The Bachelor, upon which a sea of honey-blond beach waves will certainly continue to break until the end of time. So not having much hair, or the "right kind" of it — whether by choice or circumstance — remains radical. It can also be pretty or alluring or sexy or stylish or a number of other things. But it's always, certainly, a little bit radical.

On one hand, I want to roll my eyes at how regressive it is that a mere pixie cut seems like a deviation, that society still links our concept of femininity and beauty to long, flowing hair; specifically, hair that emulates a white, European texture and ideal. On the other hand, society does that. And isn't it strangely refreshing to see that a woman who boldly eschews that standard — whether because she is in a punk-rock band, or overcoming chemo, or tired of weaves and wigs, or for any other reason just living her own follicular truth — still holds power to destabilise people?

As a woman with short hair once again, I find that 16 years after my first foray into pixies, my state of being is still remarkable, in that people feel compelled to remark upon it.

One afternoon, shortly after my initial haircut, I walked my dog around our block. Our neighbourhood mail carrier seemed actually astonished by my hair that day; he stopped, literally, in his tracks.

"Wow," he said, as though he'd been confronted with a truth he suddenly realised had been obvious all along. "I really like that haircut."

"So do I," I told him, instead of "thank you."