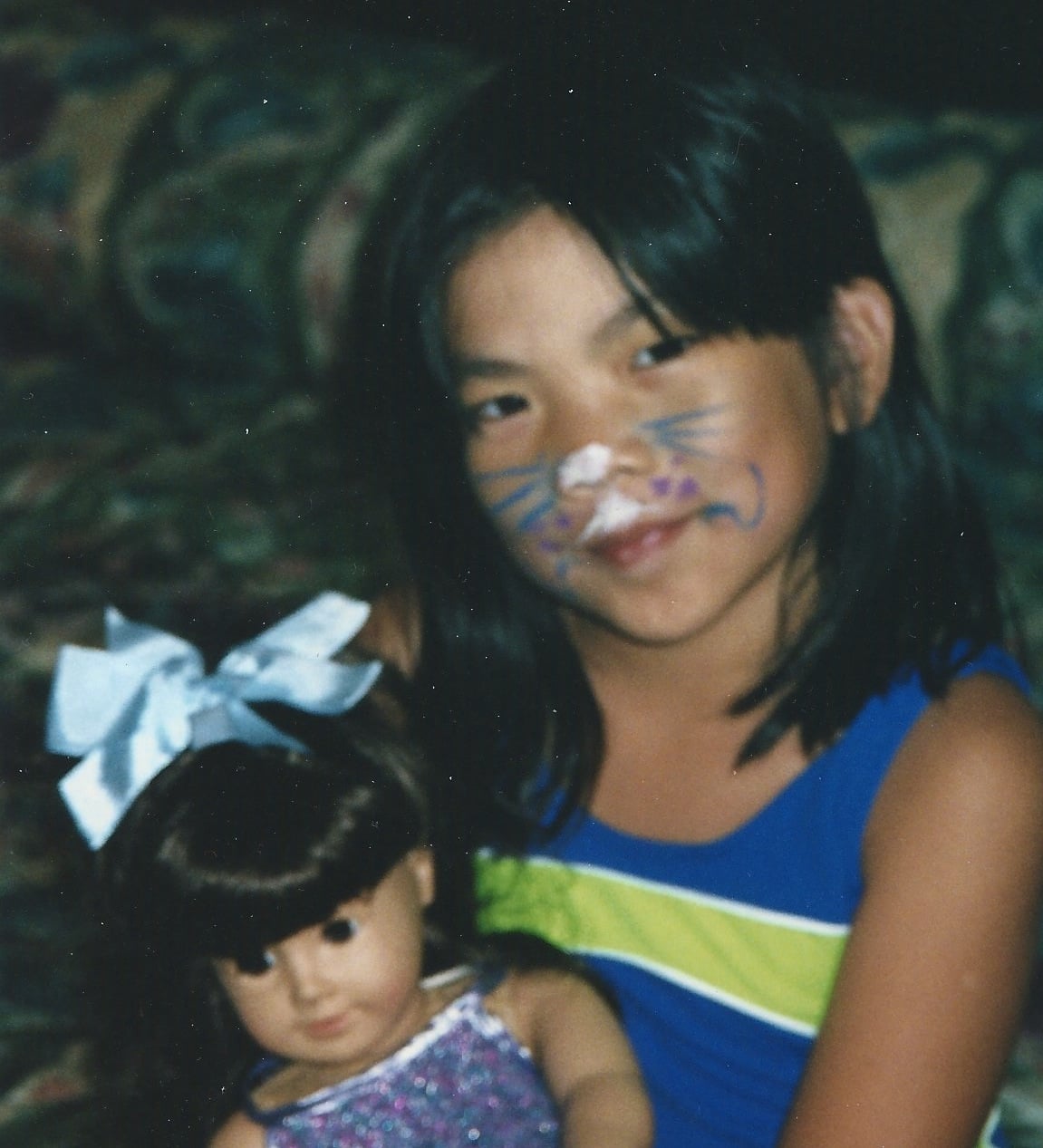

Transracial Adoption Experience

How Being a Transracial Adoptee Shaped — but Nearly Shattered — My Self-Identity

There aren't many things I recall from my seventh-grade English class, but one memory is particularly vivid. I'm standing at the front of the room, accompanied by two other kids: one of my many white peers and the only black boy (and only other student of color) in my grade. We've been called upon by our teacher to paint a visual picture of racial diversity.

While likely good-intentioned, this is one of the most defining memories in my transracial — or "interracial" — adoption experience, but not the first or last. As the China-born daughter of white parents, it was a poignant reminder that the world I was supposed to identify with was one where I didn't necessarily fit in. Let's call that phase one.

As the China-born daughter of white parents, it was a poignant reminder that the world I was supposed to identify with was one where I didn't necessarily fit in.

My adoption was never a hush topic in my family; conceptually, I've understood it as far back as my earliest memories go. One of my picture books mirrored my parents' journey bringing me home from China to Chicago at 7 months old, using vibrant illustrations and language I could comprehend. My mom was quick to answer any questions I had, too, always reassuring me that even though we weren't biologically related, my parents were still my "real" parents. That part made sense. I never struggled with abandonment issues and was lucky to feel secure in that way. But adoption is complex, and that's just one part of the narrative. My transracial adoption experience has been marbled with deep layers of confusion, resentment, and pain that narrowly derailed the development of my self-identity.

Growing up as an Asian girl with an Italian last name means my identity is not singular or easily interpreted. Defining it has often been at the hands of others, based on physical features I didn't even feel like I owned. In the overwhelmingly white spaces I was raised in, I became a token, a novelty, and a symbol of perceived "diversity" long before I understood what those things meant. Although I physically coexisted with my peers, it always felt like I was running parallel — othered, but not necessarily excluded.

Navigating public spaces has been a life lesson in chilling realities, too. When my mom and I walk into a store, get in the same car, or show up to a dinner reservation, I listen for the subtle hesitation in people's voices and study faces as they evaluate our relationship. They call her my "friend." Waiters ask if we want separate checks. When I follow her to a register, cashiers shoot me a look that says "wait your turn." These details go unnoticed by the average person, but for me, they sting every time because they're reminders that this is my forever truth. To alleviate the mental exhaustion every encounter demands, I've trained myself to audibly say "Mom" or beat people to whatever line they were going to drop.

The latter half of 2009 kicks off phase two of my transracial adoption journey. Fresh off a decade of private elementary and middle school, I landed at the most diverse public magnet high school in Chicago. Uniting students from every demographic background and neighborhood within city limits, it was the first time I wasn't surrounded by glaring whiteness. It was the first place I wasn't an automatic minority, conceptually or by the numbers. In theory, this should have been refreshing. But it was a major culture shock.

Prior to high school, I'd disassociated from my Asian identity almost entirely; it was just the way I looked. I wore this with pride, too, frequently touting that I was just "Asian on the outside but white on the inside." But now, finally surrounded by people who looked like me or had already been exposed to diverse environments, that wasn't such an immediate sell. "You're the most Americanized Asian person I've ever met," they'd say. "Do you live in Chinatown, too?"

Calling attendance with new teachers was an experience, too. Eyes beelined in my direction as they read last names like "Chen" or "Zhang." But when I replied "here" to a name that didn't match my face, reactions shifted to puzzled and hesitant. Whether or not I wanted to — and, again, at the hands of other people — I was being forced to confront the Asian identity I'd tried to abandon. But that wasn't what separated me from the crowd this time — it was my white association.

I grew to hate living in the uncomfortable in-between identity that, I decided, ultimately came down to my appearance.

I grew to hate living in the uncomfortable in-between identity that, I decided, ultimately came down to my appearance — the only "real" Asian thing about me. With limited ties to the culture that defined my features, I'd never quite be "Asian enough." But those very same features meant I'd never be "white enough," either, and I think that part hurt the most. White, I'd learned, was ideal: more straightforward, more secure, more beautiful. An identity met with fewer questions. For a long time, I was subconsciously taught I could reap those benefits because of my family, but high school reminded me that was a privilege I didn't have. Being Asian felt inferior, and that came with a lot of baggage.

As a kid, I retaliated against the things that made me feel different. I was mean and dictative so I could put other people on the outside before they did it to me. But in my teenage years, I recoiled. I became guarded and more reserved, dodged any conversations around Asianness that I didn't initiate, and prioritized friendships and activities where those details felt irrelevant. I repelled and loathed my Asian identity in equal measure. Because I began shutting out things that should've shaped who I was becoming (my cultural identity, certain relationships, a willingness to voice my feelings), I tied myself to what I knew: people and things I loved, the stability of the life I grew up living, and Chicago, my home. Eventually they unraveled, too. Enter phase three.

College marks the beginning of a half decade of my life in constant limbo. I transferred schools twice in a year; I became estranged from my father and rode out a turbulent year and a half of my parents' divorce; I ended a series of once-pivotal friendships and went through my first breakup. Most importantly, my physical ties to Chicago were cut in individual threads as I left for school, later moved to New York, and watched my mom retire to Florida shortly after. How Chicago fit into my life was the only thing I felt 100 percent certain about it. I'd made it my foundation, and the loss felt devastating and sudden.

Really, though, it was a blessing in disguise. The blank slate I was left with gave me free space to reboot, define (or redefine) myself, and start making sense of my adoption — finally on my own terms. Around that same time, inquiries about my Asian ancestry — "What kind of Asian are you, anyways?" — reached an all-time high, gradually helping turn resentment into appreciation for all the ways adoption and my Asian identity made me unique. And it was more than just my appearance or how my family is structured; it was about the voice I could have, the stories I could tell, and what doing so could mean for other people. Instead of being defensive or dismissive, I could use questions and conversations to educate and share a perspective I know is worth being part of the conversation. Seeing that growth in myself has been palpable and profound.

When I reflect on my 23 years, I'm sad for the five-, 12-, and 17-year-old versions of my younger self who felt isolated by their pain. Now, though I've still got work to do, I feel strong and supported, so my heart hurts for everyone who has or will experience the world in a similar way — quietly and alone. All that said, it's really the parents I write this for.

Strokes of luck and privilege mean that, in a lot of ways, I have an incredible life, where there's love and security and the indescribable feeling of being a gift in someone else's life. I understand my birth parents may not have echoed these sentiments, and knowing all of this sometimes makes me feel guilty for ever being angry. But I still need to say this: amid all the highs of welcoming a child into your lives, please don't let yourself be blindsided to the lows and what it really means to raise a person who, because of their race, will be viewed and treated in ways you can't understand.

Being discriminated against, fetishized, and the target of racial slurs and jokes for features I hadn't yet claimed was one thing. Then it was discovering that the beauty world and Hollywood didn't represent girls who looked like me, or becoming an automatic sounding board for other people's criticisms and opinions. I can clearly remember how, when, and where I've experienced each one, and how they've influenced my understanding of who I was. These things are important. But even more important is that I've realized I can write my own self-identity, so it's on me to decide how and where they fit.

Understanding my identity has always been the big empty void in my life. I've wasted a lot of energy being upset over it and spent infinite time trying to neutralize the dichotomy of my conflicting realities. Now I realize that, as a transracial adoptee, my identity — the deepest layers of it — will always be one of the first talking points when I meet new people. It's put on display in fragments of black hair, monolid eyes, an Italian last name, and the family I'm surrounded by. Those will never change. But it's finding the right things to say out loud and tell myself that strike the balance of feeling seen, heard, and fulfilled. And that's how I'm starting phase four.