Why I'm Giving Up True Crime

I'm About to Become a Mother, and It's Time to Give Up True Crime

Image Source: Getty / Taro Yamasaki

I was walking my dog the other day when a gardener said hello to us. He was shrouded behind some trees, but my first thought wasn't "Hello, kind stranger," it was "GET AWAY FROM ME." It was around 11 a.m., the sun was shining on my tree-lined street, and I had my 87-pound Labrador by my side — my baby bump is also just beginning to show from underneath baggy sweatshirts. It occurred to me in that moment, and many before it (if I'm being honest), that I might not be OK.

For the past few years, I've been in a deep hole of true crime. I try to balance out the darkness with fluffy comedies and reality shows, but when I wake up to a bump in the night, I'm not thinking about Superstore or Vanderpump Rules. No, I'm fixated on how we'll never really know how many women Ted Bundy killed during his spree in the '70s and obsessing about what really happened to poor Madeleine McCann.

"I couldn't get past the first story about Kelly, who accepted a man's offer to help carry her groceries to her apartment and ended up being raped and nearly killed."

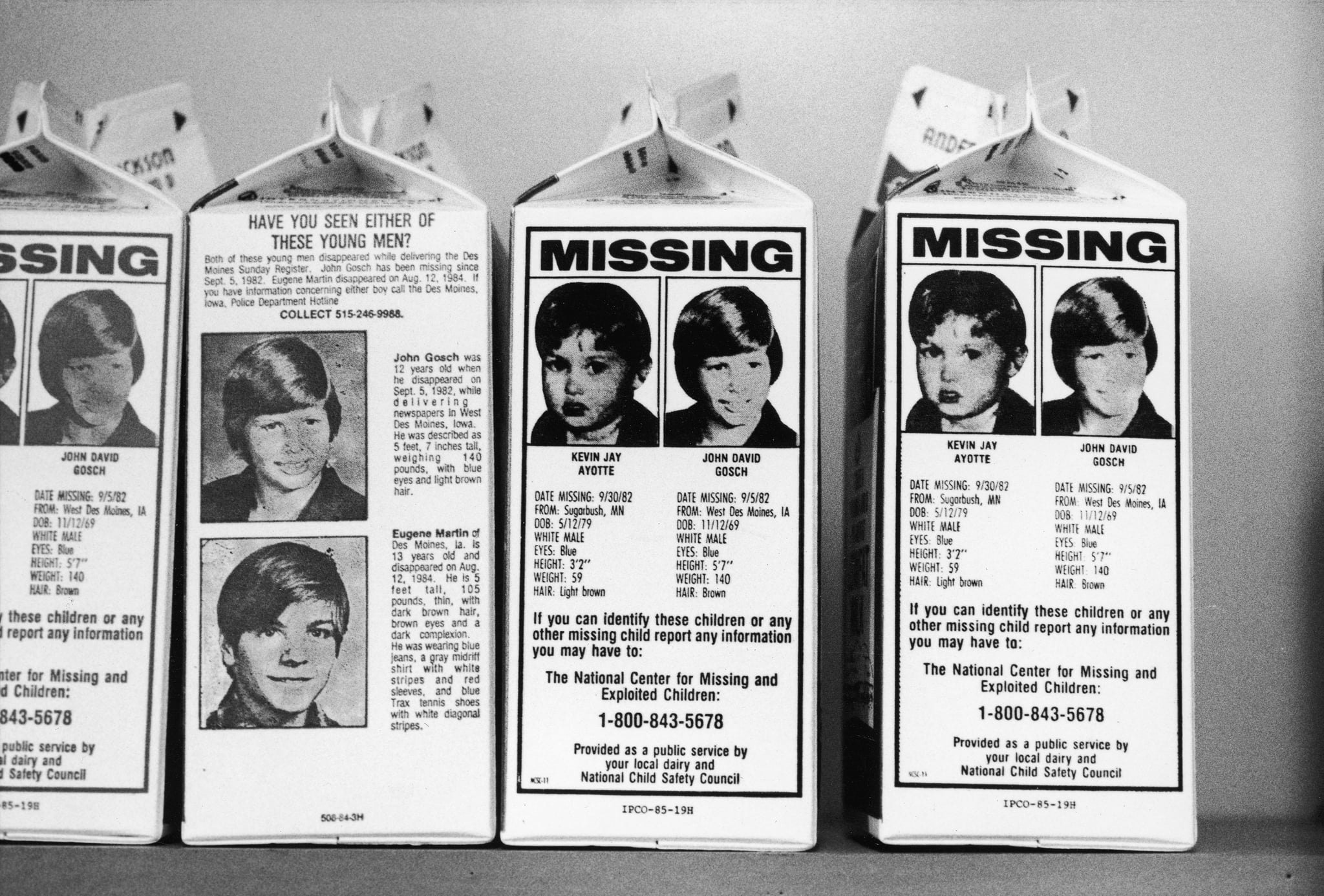

This feeling of impending disaster isn't a recent development for me. For better or worse, my parents instilled a sense of "stranger danger" in me as a child. My mother had been scarred by the abduction of 12-year-old Polly Klaas in 1993. Klass was taken from a slumber party at knife-point, strangled, and buried in a shallow grave — less than an hour from my home. It was a brutal awakening for many parents in the San Francisco Bay Area that they couldn't protect their children from the evils of the world, and it was enough for my mother to put a second twin bed across my room, where she would sleep most nights.

Of course, there are the little things that scared me, too. My brother used to watch Unsolved Mysteries, which taught me at a young age to never jog at night because you will be dragged into a forest, never to be seen again. My dad and stepmom sent me to college with a book called The Gift of Fear, a guide to listening to your "survival signals." I couldn't get past the first story about Kelly, who accepted a man's offer to help carry her groceries to her apartment and ended up being raped and nearly killed.

Image Source: Getty / Vasco Celio / AFP

In college, I learned about cultivation theory, which asserts that the more time we spend watching a certain type of television, the more likely we are to assume that reality mirrors the TV world. In short: if I'm watching and listening to true crime all the time, eventually my brain is going to tell me that random, violent crime is happening all around me all the time. While there are some criticisms of the study, it's been proven that even watching the nightly news can lead to increased feelings of anxiety and fear. I know this logically, but it's as if my body hasn't fully digested it.

Why, you may ask, would someone who is already prone to feelings of paranoia subject herself to 18 entire seasons of Law & Order: Special Victims Unit (many episodes of which are inspired by true stories)? Why would she seek out podcasts dedicated to murder? Why would she watch every true crime documentary that Netflix has to offer? Maybe it's because Olivia Benson always wins in the end, or that the podcasts serve as a reminder that Charles Manson and Ted Bundy are long dead. Then again, perhaps it's because if I know these horrific crimes happening to someone else, they aren't happening to me.

But it's not just about me anymore.

My husband and I are welcoming our first child, a daughter, in a few months. The poor girl is already being exposed to elevated levels of cortisol (a stress hormone triggered by fear) every time I walk past a white van. While the long-term effects of cortisol on a fetus aren't fully understood, studies do show that it poses an increased risk for preterm labor.

Looking further ahead, I don't want my daughter growing up assuming that a stranger is poised outside her window, ready to slit the screen and pluck her from her bed, as happened to 10-year-old Louise Bell in 1982. There has to be a happy medium between teaching my child to trust her gut instincts and making her feel like a predator is around every corner. My paranoia may have stemmed from my mother's fears, but I certainly haven't done my brain any favours by constantly pummeling it with true stories of murder, rape, and torture.

As I type this, my baby is thrashing around in my belly, kicking, punching, and reminding me that one day, she will be fully capable of defending herself — God forbid she even need to. In the meantime, it's up to me, my husband, and our community to protect her. That doesn't mean burying my head in the sand and leaving her in a park to fend for herself (I'm not insane), it means teaching her skills to identify suspicious behaviour and speak up, loudly. It means walking confidently down the street so she learns to do so as well. It also means passing on to her that the vast majority of people are good, and that she is surrounded by trustworthy people who love her.

And right now, as I prepare for this wonderful new person to enter into my life, it means keeping an eye on local news but taking a step back from media that turns me into a paranoid weirdo.